1

The Italians say, "Traduttore traditore" ("[the] translator [is a] traitor") - as a writer, translated writer and translator myself, I have experienced that publishers do not hesitate to ride roughshod over my own or any other literary texts. I hate it! There is no limit to publishers' and their editors' venal cruelty. They cut, add, change, make a text more sexually provocative or less, change the point of view, the tenses, remove politically charged or what they perceive as politically incorrect content. There is no editorial horror a writer can think of which hasn't been done by a publisher. That literary works are works of art, publishers will repeat in every interview they give, but most wouldn't hesitate to retouch Mona Lisa's face to sell more tickets to the Louvre.

2

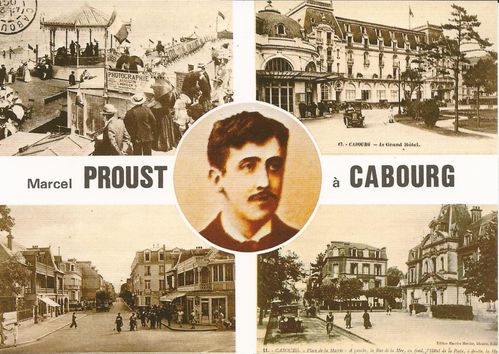

Marcel Proust was gay. In his À la recherche du temps perdu, the hero calls his friend Gilbert "Gilberte", his lover Albert "Albertine", other gay men become "girls". My adaption translates Proust's gay-speak into plain English. That I had to change little more than the gender – Proust's "girls" wear no skirts and act less feminine than real "queens" – proves that his "girls" really are boys:

"The platform of the band-stand provided, above his head, a natural and tempting springboard, across which, without a moment's hesitation, the eldest of the little band began to run; he jumped over the terrified old man, whose yachting cap was brushed by the nimble feet, to the great delight of the other boys, especially of a pair of green eyes in a 'dashing' face, which expressed, for that bold act, an admiration and a merriment in which I seemed to discern a trace of timidity, a shamefaced and blustering timidity which did not exist in the others. "Oh, the poor old man; he makes me sick; he looks half dead;" said a boy with a croaking voice, but with more sarcasm than sympathy."

Could a girl in a light linen summer dress jump from the band-stand over an old man seated below on a chair? And what about the girl's croaking voice (French d’une voix rogommeuse, literally "with the voice of a drunkard")?

3

C. K. Scott Moncrieff's dusty translation of Proust's À l'ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs with its exaggerations ("towering rage" for French facheé; "Like a dying duck in a thunderstorm!" for Proust's prosaic une poule mouillée) and attempts to make the text more heterosexual ("bent sullenly over her bosom" for inclinée d’un air boudeur; "blue-stocking friend" for l’amie si savante) is not Marcel Proust's work of art. To retouch such a translation is no sacrilege. For In the Shadow of Boys in Bloom, I changed the gender of Marcel's boyfriends and some other obvious "girls", replaced a few "dresses" with "suits" - with respect for the spirit of the story and its author.

4

Literary gender-changing has a long tradition: For centuries almost all translations of poetry from today's Turkey, Iran, Syria, Lebanon, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India were and are still gender-changed to sell Western readers traditionally homoerotic poems as heterosexual poetry. I hope nobody will object if, for once, I do the reverse.

For this adaption, I encountered some wicked problems: Albert[ine] and her friends are neither genuine girls, nor always "girls", nor real boys. They are androgynous fantasy creatures who carry golf clubs and hang around in the local Casino like young men and play parlor games and ring the hotel bell when the hero wants to kiss one of them like young women. They don't mind the sun like boys and wear their hair like girls. Like the androgynous "Miss Sacripant" whom Elstir painted, they wear two hats:

"It was — this water-color — the portrait of a young [boy or girl?], by no means beautiful but of a curious type, in a close-fitting mob-cap not unlike a ‘billy-cock’ hat, trimmed with a ribbon of cherry-colored silk; in one of [his or her?] mittened hands was a lighted cigarette, while the other held, level with [his or her?] knee, a sort of broad-brimmed garden hat, nothing more than a fire screen of plaited straw to keep off the sun."

Finally, in view of the discrimination gays suffered in the militaristic France of the late 19th century, we might consider that in a more gay-friendly epoch, Marcel Proust would not have changed the "girls" he adored into women. In the Shadow of Boys in Bloom might well be the novel Proust imagined but didn't dare to write down.

IN THE SHADOW OF BOYS IN BLOOM

The Little Band

That day, as for some days past, Saint-Loup had been obliged to go to Doncières, where, until his leave finally expired, he would be on duty now until late every afternoon. I was sorry that he was not at Balbec. I had seen alight from carriages and pass, some into the ball-room of the Casino, others into the ice-cream shop, boys who at a distance had seemed to me lovely. I was passing through one of those periods of our youth, unprovided with any one definite love, vacant, in which always and in all places - as a lover the man by whose charms he is smitten - we desire, we seek, we see Beauty. Let but a single real feature - the little that one distinguishes of a man seen from afar or from behind - enable us to project the form of beauty before our eyes, we imagine that we have seen him before, our heart beats, we hasten in pursuit, and will always remain half-persuaded that it was he, provided that the man has vanished: it is only if we manage to overtake him that we realize our mistake.

Besides, as I grew more and more delicate, I was inclined to overrate the simplest pleasures because of the difficulties that sprang up in the way of my attaining them. Charming men I seemed to see all round me, because I was too tired, if it was on the beach, too shy if it was in the Casino or at a pastry-cook's, to go anywhere near them. And yet if I was soon to die I should have liked first to know the appearance at close quarters, of the prettiest boys that life had to offer, even although it should be another than myself or no one at all who was to take advantage of the offer. (I did not, in fact, appreciate the desire for possession that underlay my curiosity.) I should have had the courage to enter the ballroom if Saint-Loup had been with me. Left by myself, I was simply hanging about in front of the Grand Hotel until it was time for me to join my grandmother, when, still almost at the far end of the paved 'front' along which they projected in a discordant spot of color, I saw coming towards me five or six young men, as different in appearance and manner from all the people whom one was accustomed to see at Balbec as could have been, landed there none knew whence, a flight of gulls which performed with measured steps upon the sands - the dawdlers using their wings to overtake the rest - a movement the purpose of which seems as obscure to the human bathers, whom they do not appear to see, as it is clearly determined in their own birdish minds.

One of these strangers was pushing as he came, with one hand, his bicycle; two others carried golf-clubs; and their attire generally contrasted with that of the other boys at Balbec, some of whom, it was true, went in for games, but without adopting any special outfit.

It was the hour at which ladies and gentlemen came out every day for a turn on the 'front,' exposed to the merciless fire of the long glasses fastened upon them, as if they had each borne some disfigurement which she felt it her duty to inspect in its minutest details, by the chief magistrate's wife, proudly seated there with her back to the band-stand, in the middle of that dread line of chairs on which presently they too, actors turned critics, would come and establish themselves, to scrutinize in their turn those others who would then be filing past them. All these people who paced up and down the 'front,' tacking as violently as if it had been the deck of a ship (for they could not lift a leg without at the same time waving their arms, turning their heads and eyes, settling their shoulders, compensating by a balancing movement on one side for the movement they had just made on the other, and puffing out their faces), and who, pretending not to see so as to let it be thought that they were not interested, but covertly watching, for fear of running against the people who were walking beside or coming towards them, did, in fact, butt into them, became entangled with them, because each was mutually the object of the same secret attention veiled beneath the same apparent disdain; their love - and consequently their fear - of the crowd being one of the most powerful motives in all men, whether they seek to please other people or to astonish them, or to show them that they despise them. In the case of the solitary, his seclusion, even when it is absolute and ends only with life itself, has often as its primary cause a disordered love of the crowd, which so far overrules every other feeling that, not being able to win, when he goes out, the admiration of his hall-porter, of the passers-by, of the cabman whom he hails, he prefers not to be seen by them at all, and with that object abandons every activity that would oblige him to go out of doors.

Among all these people, some of whom were pursuing a train of thought, but if so betrayed its instability by spasmodic gestures, a roving gaze as little in keeping as the circumspect titubation of their neighbors, the boys whom I had noticed, with that mastery over their limbs which comes from perfect bodily condition and a sincere contempt for the rest of humanity, were advancing straight ahead, without hesitation or stiffness, performing exactly the movements that they wished to perform, each of their members in full independence of all the rest, the greater part of their bodies preserving that immobility which is so noticeable in a good waltz. They were now quite near me. Although each was a type different from the others, they all had beauty; but to tell the truth I had seen them for so short a time, and without venturing to look them straight in the face, that I had not yet individualized any of them. Save one, whom his straight nose, his dark complexion pointed in contrast among the rest, like (in a renaissance picture of the Epiphany) a king of Arab cast, they were known to me only, one by a pair of eyes, hard, set and mocking; another by cheeks in which the pink had that coppery tint which makes one think of geraniums; and even of these points I had not yet indissolubly attached any one to one of these boys rather than to another; and when (according to the order in which their series met the eye, marvelous because the most different aspects came next one another, because all scales of colors were combined in it, but confused as a piece of music in which I should not have been able to isolate and identify at the moment of their passage the successive phrases, no sooner distinguished than forgotten) I saw emerge a pallid oval, black eyes, green eyes, I knew not if these were the same that had already charmed me a moment ago, I could not bring them home to any one boy whom I might thereby have set apart from the rest and so identified. And this want, in my vision, of the demarcations which I should presently establish between them sent flooding over the group a wave of harmony, the continuous transfusion of a beauty fluid, collective and mobile.

It was not perhaps, in this life of ours, mere chance that had, in forming this group of friends, chosen them all of such beauty; perhaps these boys (whose attitude was enough to reveal their nature, bold, frivolous and hard), extremely sensitive to everything that was ludicrous or ugly, incapable of yielding to an intellectual or moral attraction, had naturally felt themselves, among companions of their own age, repelled by all those in whom a pensive or sensitive disposition was betrayed by shyness, awkwardness, constraint, by what, they would say, 'didn't appeal' to them, and from such had held aloof; while they attached themselves, on the other hand, to others to whom they were drawn by a certain blend of grace, suppleness, and physical neatness, the only form in which they were able to picture the frankness of a seductive character and the promise of pleasant hours in one another's company. Perhaps, too, the class to which they belonged, a class which I should not have found it easy to define, was at that point in its evolution at which, whether thanks to its growing wealth and leisure, or thanks to new athletic habits, extended now even to certain plebeian elements, and a habit of physical culture to which had not yet been added the culture of the mind, a social atmosphere, comparable to that of smooth and prolific schools of sculpture, which have not yet gone in for tortured expressions, produces naturally and in abundance fine bodies with fine legs, fine hips, wholesome and reposeful faces, with an air of agility and guile. And were they not noble and calm models of human beauty that I beheld there, outlined against the sea, like statues exposed to the sunlight upon a Grecian shore?

Just as if, in the heart of their band, which progressed along the 'front' like a luminous comet, they had decided that the surrounding crowd was composed of creatures of another race whose sufferings even could not awaken in them any sense of fellowship, they appeared not to see them, forced those who had stopped to talk to step aside, as though from the path of a machine that had been set going by itself, so that it was no good waiting for it to get out of their way, their utmost sign of consciousness being when, if some old gentleman of whom they did not admit the existence and thrust from them the contact, had fled with a frightened or furious, but a headlong or ludicrous motion, they looked at one another and smiled. They had, for whatever did not form part of their group, no affectation of contempt; their genuine contempt was sufficient. But they could not set eyes on an obstacle without amusing themselves by crossing it, either in a running jump or with both feet together, because they were all filled to the brim, exuberant with that youth which we need so urgently to spend that even when we are unhappy or unwell, obedient rather to the necessities of our age than to the mood of the day, we can never pass anything that can be jumped over or slid down without indulging ourselves conscientiously, interrupting, interspersing our slow progress - as Chopin his most melancholy phrase - with graceful deviations in which caprice is blended with virtuosity. The wife of an elderly banker, after hesitating between various possible exposures for her husband, had settled him on a folding chair, facing the 'front,' sheltered from wind and sun by the band-stand. Having seen him comfortably installed there, she had gone to buy a newspaper which she would read aloud to him, to distract him - one of her little absences which she never prolonged for more than five minutes, which seemed long enough to him but which she repeated at frequent intervals so that this old husband on whom she lavished an attention that she took care to conceal, should have the impression that he was still quite alive and like other people and was in no need of protection. The platform of the band-stand provided, above his head, a natural and tempting springboard, across which, without a moment's hesitation, the eldest of the little band began to run; he jumped over the terrified old man, whose yachting cap was brushed by the nimble feet, to the great delight of the other boys, especially of a pair of green eyes in a 'dashing' face, which expressed, for that bold act, an admiration and a merriment in which I seemed to discern a trace of timidity, a shamefaced and blustering timidity which did not exist in the others. "Oh, the poor old man; he makes me sick; he looks half dead;" said a boy with a croaking voice, but with more sarcasm than sympathy. They walked on a little way, then stopped for a moment in the middle of the road, with no thought whether they were impeding the passage of other people, and held a council, a solid body of irregular shape, compact, unusual and shrill, like birds that gather on the ground at the moment of flight; then they resumed their leisurely stroll along the 'front,' against a background of sea.

By this time their charming features had ceased to be indistinct and impersonal. I had dealt them like cards into so many heaps to compose (failing their names, of which I was still ignorant) the big one who had jumped over the old banker; the little one who stood out against the horizon of sea with his plump and rosy cheeks, his green eyes; the one with the straight nose and dark complexion, in such contrast to all the rest; another, with a white face like an egg on which a tiny nose described an arc of a circle like a chicken's beak; yet another, wearing a hooded cape (which gave him so poverty-stricken an appearance, and so contradicted the smartness of the figure beneath that the explanation which suggested itself was that this boy must have parents of high position who valued their self-esteem so far above the visitors to Balbec and the sartorial elegance of their own children that it was a matter of the utmost indifference to them that their son should stroll on the 'front' dressed in a way which humbler people would have considered too modest); a boy with brilliant, laughing eyes and plump, colorless cheeks, a black polo-cap pulled down over his face, who was pushing a bicycle with so exaggerated a movement of his hips, with an air borne out by his language, which was so typically of the gutter and was being shouted so loud, when I passed him (although among his expressions I caught that irritating 'live my own life') that, abandoning the hypothesis which his friend's hooded cape had made me construct, I concluded instead that all these boys belonged to the population which frequents the racing-tracks, and must be the very juvenile lovers of professional bicyclists. In any event, in none of my suppositions was there any possibility of their being virtuous. At first sight - in the way in which they looked at one another and smiled, in the insistent stare of the one with the dull cheeks - I had grasped that they were not. Besides, my grandmother had always watched over me with a delicacy too timorous for me not to believe that the sum total of the things one ought not to do was indivisible or that boys who were lacking in respect for their elders would suddenly be stopped short by scruples when there were pleasures at stake more tempting than that of jumping over an octogenarian.

Though they were now separately identifiable, still the mutual response which they gave one another with eyes animated by self-sufficiency and the spirit of comradeship, in which were kindled at every moment now the interest now the insolent indifference with which each of them sparkled according as his glance fell on one of his friends or on passing strangers, that consciousness, moreover, of knowing one another intimately enough always to go about together, by making them a 'band apart' established between their independent and separate bodies, as slowly they advanced, a bond invisible but harmonious, like a single warm shadow, a single atmosphere making of them a whole as homogeneous in its parts as it was different from the crowd through which their procession gradually wound.

For an instant, as I passed the dark one with the fat cheeks who was wheeling a bicycle, I caught him smiling, sidelong glance, aimed from the center of that inhuman world which enclosed the life of this little tribe, an inaccessible, unknown world to which the idea of what I was could certainly never attain nor find a place in it. Wholly occupied with what his companions were saying, this young man in his polo-cap, pulled down very low over his brow, had he seen me at the moment in which the dark ray emanating from his eyes had fallen on me? In the heart of what universe did he distinguish me? It would have been as hard for me to say as, when certain peculiarities are made visible, thanks to the telescope, in a neighboring planet, it is difficult to arrive at the conclusion that human beings inhabit it, that they can see us, or to say what ideas the sight of us can have aroused in their minds.

If we thought that the eyes of a boy like that were merely two glittering sequins of mica, we should not be athirst to know him and to unite his life to ours. But we feel that what shines in those reflecting discs is not due solely to their material composition; that it is, unknown to us, the dark shadows of the ideas that the creature is conceiving, relative to the people and places that he knows - the turf of racecourses, the sand of cycling tracks over which, pedaling on past fields and woods, he would have drawn me after him, that little peri, more seductive to me than she of the Persian paradise - the shadows, too, of the home to which he will presently return, of the plans that he is forming or that others have formed for him; and above all that it is he, with his desires, his sympathies, his revulsions, his obscure and incessant will. I knew that I should never possess this young cyclist if I did not possess also what there was in his eyes. And it was consequently his whole life that filled me with desire; a sorrowful desire because I felt that it was not to be realized, but exhilarating, because what had hitherto been my life, having ceased of a sudden to be my whole life, being no more now than a little part of the space stretching out before me, which I was burning to cover and which was composed of the lives of these boys, offered me that prolongation, that possible multiplication of oneself which is happiness. And no doubt the fact that we had, these boys and I, not one habit - as we had not one idea - in common, was to make it more difficult for me to make friends with them and to please them. But perhaps, also, it was thanks to those differences, to my consciousness that there did not enter into the composition of the nature and actions of these boys a single element that I knew or possessed, that there came in place of my satiety a thirst - like that with which a dry land burns - for a life which my soul, because it had never until now received one drop of it, would absorb all the more greedily in long draughts, with a more perfect imbibition.

I had looked so closely at the dark cyclist with the bright eyes that he seemed to notice my attention, and said to the biggest of the boys something that I could not hear. To be honest, this dark one was not the one that pleased me most, simply because he was dark and because (since the day on which, from the little path by Tansonville, I had seen Gilbert) a boy with reddish hair and a golden skin had remained for me the inaccessible ideal. But Gilbert himself, had I not loved him principally because he had appeared to me haloed with that aureole of being the friend of Bergotte, of going with him to look at old cathedrals? And in the same way could I not rejoice at having seen this dark boy look at me (which made me hope that it would be easier for me to get to know him first), for he would introduce me to the others, to the pitiless one who had jumped over the old man's head, to the cruel one who had said "He makes me sick, poor old man!" - to all of them in turn, among whom, moreover, he had the distinction of being their inseparable companion? And yet the supposition that I might someday be the friend of one or other of these boys, that their eyes, whose incomprehensible gaze struck me now and again, playing upon me unawares, like the play of sunlight upon a wall, might ever, by a miraculous alchemy, allow to interpenetrate among their ineffable particles the idea of my existence, some affection for my person, that I myself might someday take my place among them in the evolution of their course by the sea's edge - that supposition appeared to me to contain within it a contradiction as insoluble as if, standing before some classical frieze or a fresco representing a procession, I had believed it possible for me, the spectator, to take my place, beloved of them, among the godlike hierophants.

The happiness of knowing these boys was, then, not to be realized. Certainly it would not have been the first of its kind that I had renounced. I had only to recall the numberless strangers whom, even at Balbec, the carriage bowling away from them at full speed had forced me forever to abandon. And indeed the pleasure that was given me by the little band, as noble as if it had been composed of Hellenic virgins, came from some suggestion that there was in it of the flight of passing figures along a road. This fleetingness of persons who are not known to us, who force us to put out from the harbor of life, in which the men whose society we frequent have all, in course of time, laid bare their blemishes, urges us into that state of pursuit in which there is no longer anything to arrest the imagination. But to strip our pleasures of imagination is to reduce them to their own dimensions, that is to say to nothing. Offered me by one of those procurers (whose good offices, all the same, the reader has seen that I by no means scorned), withdrawn from the element which gave them so many fine shades and such vagueness, these boys would have enchanted me less. We must have imagination, awakened by the uncertainty of being able to attain our object, to create a goal which hides our other goal from us, and by substituting for sensual pleasures the idea of penetrating into a life prevents us from recognizing that pleasure, from tasting its true savor, from restricting it to its own range.

There must be, between us and the fish which, if we saw it for the first time cooked and served on a table, would not appear worth the endless trouble, craft and stratagem that are necessary if we are to catch it, interposed, during our afternoons with the rod, the ripple to whose surface come wavering, without our quite knowing what we intend to do with them, the burnished gleam of flesh, the indefiniteness of a form, in the fluidity of a transparent and flowing azure.

These boys benefited also by that alteration of social values characteristic of seaside life. All the advantages which, in our ordinary environment, extend and magnify our importance, we there find to have become invisible, in fact to be eliminated; while on the other hand the people whom we suppose, without reason, to enjoy similar advantages appear to us amplified to artificial dimensions. This made it easy for strange men generally, and to-day for these boys in particular, to acquire an enormous importance in my eyes, and impossible to make them aware of such importance as I might myself possess.

But if there was this to be said for the excursion of the little band, that it was but an excerpt from the innumerable flight of passing men, which had always disturbed me, their flight was here reduced to a movement so slow as to approach immobility. Now, precisely because, in a phase so far from rapid, faces no longer swept past me in a whirlwind, but calm and distinct still appeared beautiful, I was prevented from thinking as I had so often thought when Mrs. de Villeparisis' carriage bore me away that, at closer quarters, if I had stopped for a moment, certain details, a pitted skin, drooping nostrils, a silly gape, a grimace of a smile, an ugly figure might have been substituted, in the face and body of the man, for those that I had doubtless imagined; for there had sufficed a pretty outline, a glimpse of a fresh complexion, for me to add, in entire good faith, a fascinating shoulder, a delicious glance of which I carried in my mind for ever a memory or a preconceived idea, these rapid decipherings of a person whom we see in motion exposing us thus to the same errors as those too rapid readings in which, on a single syllable and without waiting to identify the rest, we base instead of the word that is in the text a wholly different word with which our memory supplies us. It could not be so with me now. I had looked well at them all; each of them I had seen, not from every angle and rarely in full face, but all the same in two or three aspects different enough to enable me to make either the correction or the verification, to take a 'proof of the different possibilities of line and color that are hazarded at first sight, and to see persist in them, through a series of expressions, something unalterably material. I could say to myself with conviction that neither in Paris nor at Balbec, in the most favorable hypotheses of what might have happened, even if I had been able to stop and talk to them, the passing men who had caught my eye, had there ever been one whose appearance, followed by his disappearance without my having managed to know him, had left me with more regret than would these, had given me the idea that his friendship might be a thing so intoxicating. Never, among actors nor among peasants nor among boys from a convent school had I beheld anything so beautiful, impregnated with so much that was unknown, so inestimably precious, so apparently inaccessible. They were, of the unknown and potential happiness of life, an illustration so delicious and in so perfect a state that it was almost for intellectual reasons that I was desperate with the fear that I might not be able to make, in unique conditions which left no room for any possibility of error, proper trial of what is the most mysterious thing that is offered to us by the beauty which we desire and console ourselves for never possessing, by demanding pleasure - as Swann had always refused to do before Odette's day - from men whom we have not desired, so that, indeed, we die without having ever known what that other pleasure was. No doubt it was possible that it was not in reality an unknown pleasure, that on a close inspection its mystery would dissipate and vanish, that it was no more than a projection, a mirage of desire. But in that case I could blame only the compulsion of a law of nature - which if it applied to these boys would apply to all - and not the imperfection of the object. For it was that which I should have chosen above all others, feeling quite certain, with a botanist's satisfaction, that it was not possible to find collected anywhere rarer specimens than these young flowers who were interrupting at this moment before my eyes the line of the sea with their slender hedge, like a bower of Pennsylvania roses adorning a garden on the brink of a cliff, between which is contained the whole tract of ocean crossed by some steamer, so slow in gliding along the blue and horizontal line that stretches from one stem to the next that an idle butterfly, dawdling in the cup of a flower which the moving hull has long since passed, can, if it is to fly and be sure of arriving before the vessel, wait until nothing but the tiniest slice of blue still separates the questing prow from the first petal of the flower towards which it is steering.

I went indoors because I was to dine at Rivebelle with Robert, and my grandmother insisted that on those evenings, before going out, I must lie down for an hour on my bed, a rest which the Balbec doctor presently ordered me to extend to the other evenings also.

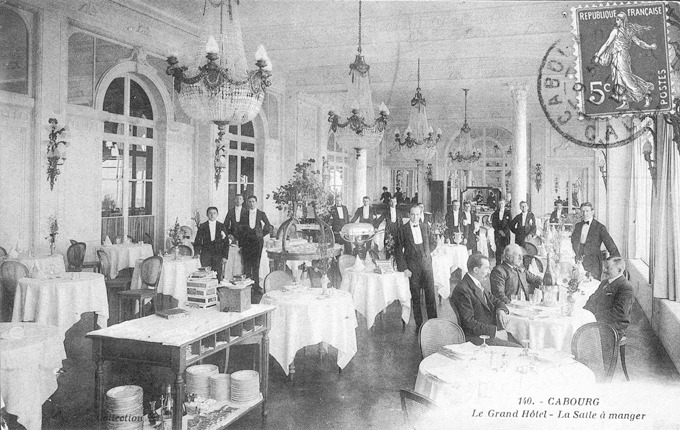

However, there was no need, when one went indoors, to leave the 'front' and to enter the hotel by the hall, that is to say from behind. By virtue of an alteration of the clock which reminded me of those Saturdays when, at Combray, we used to have luncheon an hour earlier, now with summer at the full the days had become so long that the sun was still high in the heavens, as though it were only tea-time, when the tables were being laid for dinner in the Grand Hotel. And so the great sliding windows were kept open from the ground. I had but to step across a low wooden sill to find myself in the dining-room, through which I walked and straight across to the lift.

As I passed the office I addressed a smile to the manager, and with no shudder of disgust gathered one for myself from his face which, since I had been at Balbec, my comprehensive study of it was injecting and transforming, little by little, like a natural history preparation. His features had become familiar to me, charged with a meaning that was of no importance but still intelligible, like a script which one can read, and had ceased in any way to resemble these queer, intolerable characters which his face had presented to me on that first day, when I had seen before me a personage now forgotten, or, if I succeeded in recalling him, unrecognizable, difficult to identify with this insignificant and polite personality of which the other was but a caricature, a hideous and rapid sketch. Without either the shyness or the sadness of the evening of my arrival I rang for the attendant, who no longer stood in silence while I rose by his side in the lift as in a mobile thoracic cage propelled upwards along its ascending pillar, but repeated:

"There aren't the people now there were a month back. They're beginning to go now; the days are drawing in." He said this not because there was any truth in it but because, having an engagement, presently, for a warmer part of the coast, he would have liked us all to leave, so that the hotel could be shut up and he have a few days to himself before 'rejoining' in his new place. 'Rejoin' and 'new' were not, by the way, incompatible terms, since, for the lift-boy, 'rejoin' was the usual form of the verb 'to join.' The only thing that surprised me was that he condescended to say 'place,' for he belonged to that modern proletariat which seeks to efface from our language every trace of the rule of domesticity. A moment later, however, he informed me that in the 'situation' which he was about to 'rejoin,' he would have a smarter 'tunic' and a better 'salary,' the words 'livery' and 'wages' sounding to him obsolete and unseemly. And as, by an absurd contradiction, the vocabulary has, through thick and thin, among us 'masters,' survived the conception of inequality, I was always failing to understand what the lift-boy said. For instance, the only thing that interested me was to know whether my grandmother was in the hotel. Now, forestalling my questions, the lift-boy would say to me: "That lady has just gone out from your rooms." I was invariably taken in; I supposed that he meant my grandmother. "No, that lady; I think she's an employee of yours." As in the old speech of the middle classes, which ought really to be done away with, a cook is not called an employee, I thought for a moment: "But he must be mistaken. We don't own a factory; we haven't any employees." Suddenly I remembered that the title of 'employee' is, like the wearing of a moustache among waiters, a sop to their self-esteem given to servants, and realized that this lady who had just gone out must be Françoise (probably on a visit to the coffee-maker, or to watch the Belgian lady's little maid at her sewing), though even this sop did not satisfy the lift-boy, for he would say quite naturally, speaking pityingly of his own class, 'with the working man' or 'the small person,' using the same singular form as Racine when he speaks of 'the poor.' But as a rule, for my zeal and timidity of the first evening were now things of the past, I no longer spoke to the lift-boy. It was he now who stood there and received no answer during the short journey on which he threaded his way through the hotel, hollowed out inside like a toy, which extended round about us, floor by floor, the ramifications of its corridors in the depths of which the light grew velvety, lost its tone, diminished the communicating doors, the steps of the service stairs which it transformed into that amber haze, unsubstantial and mysterious as a twilight, in which Rembrandt picks out here and there a window-sill or a well-head. And on each landing a golden light reflected from the carpet indicated the setting sun and the lavatory window.

I asked myself whether the boys I had just seen lived at Balbec, and who they could be. When our desire is thus concentrated upon a little tribe of humanity which it singles out from the rest, everything that can be associated with that tribe becomes a spring of emotion and then of reflection. I had heard a lady say on the 'front': "He is a friend of the little Simonet boy" with that self-important air of inside knowledge, as who should say: "He is the inseparable companion of young La Rochefoucauld." And immediately she had detected on the face of the person to whom she gave this information a curiosity to see more of the favored person who was 'a friend of the little Simonet.' A privilege, obviously, that did not appear to be granted to all the world. For aristocracy is a relative state. And there are plenty of inexpensive little holes and corners where the son of an upholsterer is the arbiter of fashion and reigns over a court like any young Prince of Wales. I have often since then sought to recall how it first sounded for me there on the beach, that name of Simonet, still quite indefinite as to its form, which I had failed to distinguish, and also as to its significance, to the designation by it of such and such a person, or perhaps of someone else; imprinted, in fact, with that vagueness, that novelty which we find so moving in the sequel, when the name whose letters are every moment engraved more deeply on our hearts by our incessant thought of them has become (though this was not to happen to me with the name of the 'little Simonet' until several years had passed) the first coherent sound that comes to our lips, whether on waking from sleep or on recovering from a swoon, even before the idea of what o'clock it is or of where we are, almost before the word 'I,' as though the person whom it names were more 'we' even than we ourselves, and as though after a brief spell of unconsciousness the phase that is the first of all to dissolve is that in which we were not thinking of him. I do not know why I said to myself from the first that the name Simonet must be that of one of the band of boys; from that moment I never ceased to ask myself how I could get to know the Simonet family, get to know them, moreover, through people whom they considered superior to themselves (which ought not to be difficult if the boys were only common little 'bounders') so that they might not form a disdainful idea of me. For one cannot have a perfect knowledge, one cannot effect the complete absorption of a person who disdains one, so long as one has not overcome his disdain. And since, whenever the idea of men who are so different from us penetrates our senses, unless we are able to forget it or the competition of other ideas eliminates it, we know no rest until we have converted those aliens into something that is compatible with ourselves, our heart being in this respect endowed with the same kind of reaction and activity as our physical organism, which cannot abide the infusion of any foreign body into its veins without at once striving to digest and assimilate it: the little Simonet must be the prettiest of them all - he who, I felt moreover, might yet become my lover, for he was the only one who, two or three times half-turning his head, had appeared to take cognizance of my fixed stare. I asked the lift-boy whether he knew of any people at Balbec called Simonet. Not liking to admit that there was anything which he did not know, he replied that he seemed to have heard the name somewhere. As we reached the highest landing I told him to have the latest lists of visitors sent up to me.

I stepped out of the lift, but instead of going to my room I made my way farther along the corridor, for before my arrival the valet in charge of the landing, despite his horror of draughts, had opened the window at the end, which instead of looking out to the sea faced the hill and valley inland, but never allowed them to be seen, for its panes, which were made of clouded glass, were generally closed. I made a short 'station' in front of it, time enough just to pay my devotions to the view which for once it revealed over the hill against which the back of the hotel rested, a view that contained but a solitary house, planted in the middle distance, though the perspective and the evening light in which I saw it, while preserving its mass, gave it a sculptural beauty and a velvet background, as though to one of those architectural works in miniature, tiny temples or chapels wrought in gold and enamels, which serve as reliquaries and are exposed only on rare and solemn days for the veneration of the faithful. But this moment of adoration had already lasted too long, for the valet, who carried in one hand a bunch of keys and with the other saluted me by touching his verger's skull-cap, though without raising it, on account of the pure, cool evening air, came and drew together, like those of a shrine, the two sides of the window, and so shut off the minute edifice, the glistening relic from my adoring gaze. I went into my room. Regularly, as the season advanced, the picture that I found there in my window changed. At first it was broad daylight, and dark only if the weather was bad: and then, in the greenish glass which it distended with the curve of its round waves, the sea, set among the iron uprights of my window like a piece of stained glass in its leads, raveled out over all the deep rocky border of the bay little plumed triangles of an unmoving spray delineated with the delicacy of a feather or a downy breast from Pisanello's pencil, and fixed in that white, unalterable, creamy enamel which is used to depict fallen snow in Gallé's glass.

Presently the days grew shorter and at the moment when I entered my room the violet sky seemed branded with the stiff, geometrical, travelling, effulgent figure of the sun (like the representation of some miraculous sign, of some mystical apparition) leaning over the sea from the hinge of the horizon as a sacred picture leans over a high altar, while the different parts of the western sky exposed in the glass fronts of the low mahogany bookcases that ran along the walls, which I carried back in my mind to the marvelous painting from which they had been detached, seemed like those different scenes which some old master executed long ago for a confraternity upon a shrine, whose separate panels are now exhibited side by side upon the wall of a museum gallery, so that the visitor's imagination alone can restore them to their place on the predella of the reredos. A few weeks later, when I went upstairs, the sun had already set. Like the one that I used to see at Combray, behind the Calvary, when I was coming home from a walk and looking forward to going down to the kitchen before dinner, a band of red sky over the sea, compact and clear-cut as a layer of aspic over meat, then, a little later, over a sea already cold and blue like a grey mullet, a sky of the same pink as the salmon that we should presently be ordering at Rivebelle reawakened the pleasure which I was to derive from the act of dressing to go out to dinner. Over the sea, quite near the shore, were trying to rise, one beyond another, at wider and wider intervals, vapors of a pitchy blackness but also of the polish and consistency of agate, of a visible weight, so much so that the highest among them, poised at the end of their contorted stem and overreaching the center of gravity of the pile that had hitherto supported them, seemed on the point of bringing down in ruin this lofty structure already half the height of the sky, and of precipitating it into the sea. The sight of a ship that was moving away like a nocturnal traveler gave me the same impression that I had had in the train of being set free from the necessity of sleep and from confinement in a bedroom. Not that I felt myself a prisoner in the room in which I now was, since in another hour I should have left it and be getting into the carriage. I threw myself down on the bed; and, just as if I had been lying in a berth on board one of those steamers which I could see quite near to me and which, when night came, it would be strange to see stealing slowly out into the darkness, like shadowy and silent but unsleeping swans, I was on all sides surrounded by pictures of the sea.

But as often as not they were, indeed, only pictures; I forgot that below their colored expanse was hollowed the sad desolation of the beach, travelled by the restless evening breeze whose breath I had so anxiously felt on my arrival at Balbec; besides, even in my room, being wholly taken up with thoughts of the boys whom I had seen go past, I was no longer in a state of mind calm or disinterested enough to allow the formation of any really deep impression of beauty. The anticipation of dinner at Rivebelle made my mood more frivolous still, and my mind, dwelling at such moments upon the surface of the body which I was going to dress up so as to try to appear as pleasing as possible in the masculine eyes which would be scrutinizing me in the brilliantly lighted restaurant, was incapable of putting any depth behind the color of things. And if, beneath my window, the unwearying, gentle flight of sea-martins and swallows had not arisen like a playing fountain, like living fireworks, joining the intervals between their soaring rockets with the motionless white streaming lines of long horizontal wakes of foam, without the charming miracle of this natural and local phenomenon, which brought into touch with reality the scenes that I had before my eyes, I might easily have believed that they were no more than a selection, made afresh every day, of paintings which were shown quite arbitrarily in the place in which I happened to be and without having any necessary connection with that place. At one time it was an exhibition of Japanese color-prints: beside the neat disc of sun, red and round as the moon, a yellow cloud seemed a lake against which black swords were outlined like the trees upon its shore; a bar of a tender pink which I had never seen again after my first paint-box swelled out into a river on either bank of which boats seemed to be waiting high and dry for someone to push them down and set them afloat. And with the contemptuous, bored, frivolous glance of an amateur or a man hurrying through a picture gallery between two social engagements, I would say to myself: "Curious sunset, this; it's different from what they usually are but after all I've seen them just as fine, just as remarkable as this." I had more pleasure on evenings when a ship, absorbed and liquefied by the horizon so much the same in color as herself (an Impressionist exhibition this time) that it seemed to be also of the same matter, appeared as if someone had simply cut out with a pair of scissors her bows and the rigging in which she tapered into a slender filigree from the vaporous blue of the sky. Sometimes the ocean filled almost the whole of my window, when it was enlarged and prolonged by a band of sky edged at the top only by a line that was of the same blue as the sea, so that I supposed it all to be still sea, and the change in color due only to some effect of light and shade. Another day the sea was painted only in the lower part of the window, all the rest of which was so filled with innumerable clouds, packed one against another in horizontal bands, that its panes seemed to be intended, for some special purpose or to illustrate a special talent of the artist, to present a 'Cloud Study,' while the fronts of the various bookcases showing similar clouds but in another part of the horizon and differently colored by the light, appeared to be offering as it were the repetition - of which certain of our contemporaries are so fond - of one and the same effect always observed at different hours but able now in the immobility of art to be seen all together in a single room, drawn in pastel and mounted under glass. And sometimes to a sky and sea uniformly grey a rosy touch would be added with an exquisite delicacy, while a little butterfly that had gone to sleep at the foot of the window seemed to be attaching with its wings at the corner of this 'Harmony in Grey and Pink' in the Whistler manner the favorite signature of the Chelsea master. The pink vanished; there was nothing now left to look at. I rose for a moment and before lying down again drew close the inner curtains. Above them I could see from my bed the ray of light that still remained, growing steadily fainter and thinner, but it was without any feeling of sadness, without any regret for its passing that I thus allowed to die above the curtains the hour at which, as a rule, I was seated at table, for I knew that this day was of another kind than ordinary days, longer, like those arctic days which night interrupts for a few minutes only; I knew that from the chrysalis of the dusk was preparing to emerge, by a radiant metamorphosis, the dazzling light of the Rivebelle restaurant. I said to myself: "It is time"; I stretched myself on the bed, and rose, and finished dressing; and I found a charm in these idle moments, lightened of every material burden, in which while down below the others were dining I was employing the forces accumulated during the inactivity of this last hour of the day only in drying my washed body, in putting on a dinner jacket, in tying my tie, in making all those gestures which were already dictated by the anticipated pleasure of seeing again some man whom I had noticed, last time, at Rivebelle, who had seemed to be watching me, had perhaps left the table for a moment only in the hope that I would follow him; it was with joy that I enriched myself with all these attractions so as to give myself, whole, alert, willing, to a new life, free, without cares, in which I would lean my hesitations upon the calm strength of Saint-Loup, and would choose from among the different species of animated nature and the produce of every land those which, composing the unfamiliar dishes that my companion would at once order, might have tempted my appetite or my imagination. And then at the end of the season came the days when I could no longer pass indoors from the 'front' through the dining-room; its windows stood open no more, for it was night now outside and the swarm of poor folk and curious idlers, attracted by the blaze of light which they might not reach, hung in black clusters chilled by the north wind to the luminous sliding walls of that buzzing hive of glass.

There was a knock at my door; it was Aimé who had come upstairs in person with the latest lists of visitors.

Aimé could not go away without telling me that Dreyfus was guilty a thousand times over. "It will all come out," he assured me, "not this year, but next. It was a gentleman who's very thick with the General Staff, told me. I asked him if they wouldn't decide to bring it all to light at once, before the year is out. He laid down his cigarette," Aimé went on, acting the scene for my benefit, and, shaking his head and his forefinger as his informant had done, as much as to say: "We mustn't expect too much!" - "'Not this year, Aimé,' those were his very words, putting his hand on my shoulder, 'It isn't possible. But next Easter, yes!'" And Aimé tapped me gently on my shoulder, saying, "You see, I'm letting you have it exactly as he told me," whether because he was flattered at this act of familiarity by a distinguished person or so that I might better appreciate, with a full knowledge of the facts, the worth of the arguments and our grounds for hope.

It was not without a slight throb of the heart that on the first page of the list I caught sight of the words 'Simonet and family.' I had in me a store of old dream-memories which dated from my childhood, and in which all the tenderness (tenderness that existed in my heart, but, when my heartfelt it, was not distinguishable from anything else) was wafted to me by a person as different as possible from myself. This person, once again I fashioned him, utilizing for the purpose the name Simonet and the memory of the harmony that had reigned between the young bodies which I had seen displaying themselves on the beach, in a sportive procession worthy of Greek art or of Giotto. I knew not which of these boys was young Simonet, if indeed any of them were so named, but I did know that I was loved by young Simonet and that I was going, with Saint-Loup's help, to attempt to know him. Unfortunately, [Saint-Loup] having on that condition only obtained an extension of his leave, he was obliged to report for duty every day at Doncières: but to make him forsake his military duty I had felt that I might count, more even than on his friendship for myself, on that same curiosity, as a human naturalist, which I myself had so often felt - even without having seen the person mentioned, and simply on hearing someone say that there was a pretty cashier at a fruiterer's - to acquaint myself with a new variety of masculine beauty. But that curiosity I had been wrong in hoping to excite in Saint-Loup by speaking to him of my band of boys. For it had been and would long remain paralyzed in him by his love for that actor whose lover he was. And even if he had felt it lightly stirring him he would have repressed it, from an almost superstitious belief that on his own fidelity might depend that of his friend. And so it was without any promise from him that he would take an active interest in my boys that we started out to dine at Rivebelle.

At first, when we arrived there, the sun used just to have set, but it was light still; in the garden outside the restaurant, where the lamps had not yet been lighted, the heat of the day fell and settled, as though in a vase along the sides of which the transparent, dusky jelly of the air seemed of such consistency that a tall rose-tree fastened against the dim wall which it streaked with pink veins, looked like the arborescence that one sees at the heart of an onyx. Presently night had always fallen when we left the carriage, often indeed before we started from Balbec if the evening was wet and we had put off sending for the carriage in the hope of the weather's improving. But on those days it was without any sadness that I listened to the wind howling, I knew that it did not mean the abandonment of my plans, imprisonment in my bedroom; I knew that in the great dining-room of the restaurant, which we would enter to the sound of the music of the gypsy band, the innumerable lamps would triumph easily over darkness and chill, by applying to them their broad cauterizes of molten gold, and I jumped light-heartedly after Saint-Loup into the closed carriage which stood waiting for us in the rain. For some time past the words of Bergotte, when he pronounced himself positive that, in spite of all I might say, I had been created to enjoy, pre-eminently, the pleasures of the mind, had restored to me, with regard to what I might succeed in achieving later on, a hope that was disappointed afresh every day by the boredom that I felt on setting myself down before a writing-table to start work on a critical essay or a novel. "After all," I said to myself, "possibly the pleasure that its author has found in writing it is not the infallible test of the literary value of a page; it may be only an accessory, one that is often to be found superadded to that value, but the want of which can have no prejudicial effect on it. Perhaps some of the greatest masterpieces were written yawning." My grandmother set my doubts at rest by telling me that I should be able to work and should enjoy working as soon as my health improved. And, our doctor having thought it only prudent to warn me of the grave risks to which my state of health might expose me, and having outlined all the hygienic precaution that I ought to take to avoid any accident - I subordinated all my pleasures to an object which I judged to be infinitely more important than them, that of becoming strong enough to be able to bring into being the work which I had, possibly, within me; I had been exercising over myself, ever since I had come to Balbec, a scrupulous and constant control. Nothing would have induced me, there, to touch the cup of coffee which would have robbed me of the night's sleep that was necessary if I was not to be tired next day. But as soon as we reached Rivebelle, immediately, what with the excitement of a new pleasure, and finding myself in that different zone into which the exception to our rule of life takes us after it has cut the thread, patiently spun throughout so many days, that was guiding us towards wisdom - as though there were never to be any such thing as to-morrow, nor any lofty aims to be realized, vanished all that exact machinery of prudent hygienic measures which had been working to safeguard them. A waiter was offering to take my coat, whereupon Saint-Loup asked: "You're sure you won't be cold? Perhaps you'd better keep it: it's not very warm in here."

"No, no," I assured him; and perhaps I did not feel the cold; but however that might be, I no longer knew the fear of falling ill, the necessity of not dying, the importance of work. I gave up my coat; we entered the dining-room to the sound of some warlike march played by the gypsies, we advanced between two rows of tables laid for dinner as along an easy path of glory, and, feeling a happy glow imparted to our bodies by the rhythms of the orchestra which rendered us its military honors, gave us this unmerited triumph, we concealed it beneath a grave and frozen mien, beneath a languid, casual gait, so as not to be like those music-hall 'mashers' who, having wedded a ribald verse to a patriotic air, come running on to the stage with the martial countenance of a victorious general.

From that moment I was a new man, who was no longer my grandmother's grandson and would remember her only when it was time to get up and go, but the brother, for the time being, of the waiters who were going to bring us our dinner.

The dose of beer - all the more, that of champagne - which at Balbec I should not have ventured to take in a week, albeit to my calm and lucid consciousness the flavor of those beverages represented a pleasure clearly appreciable, since it was also one that could easily be sacrificed, I now imbibed at a sitting, adding to it a few drops of port wine, too much distracted to be able to taste it, and I gave the violinist who had just been playing the two Louis which I had been saving up for the last month with a view to buying something, I could not remember what. Several of the waiters, set going among the tables, were flying along at full speed, each carrying on his outstretched palms a dish which it seemed to be the object of this kind of race not to let fall. And in fact the chocolate soufflés arrived at their destination unspilled, the potatoes à l'anglaise, in spite of the pace which ought to have sent them flying, came arranged as at the start round the Pauilhac lamb. I noticed one of these servants, very tall, plumed with superb black locks, his face dyed in a tint that suggested rather certain species of rare birds than a human being, who, running without pause (and, one would have said, without purpose) from one end of the room to the other, made me think of one of those macaws which fill the big aviaries in zoological gardens with their gorgeous coloring and incomprehensible agitation. Presently the spectacle assumed an order, in my eyes at least, growing at once more noble and calmer. All this dizzy activity became fixed in a quiet harmony. I looked at the round tables whose innumerable assemblage filled the restaurant like so many planets as planets are represented in old allegorical pictures. Moreover, there seemed to be some irresistibly attractive force at work among these divers stars, and at each table the diners had eyes only for the tables at which they were not sitting, except perhaps some wealthy amphitryon who, having managed to secure a famous author, was endeavoring to extract from him, thanks to the magic properties of the turning table, a few unimportant remarks at which his guests [Martin Fr1] marveled. The harmony of these astral tables did not prevent the incessant revolution of the countless servants who, because instead of being seated like the diners they were on their feet, performed their evolutions in a more exalted sphere. No doubt they were running, one to fetch the hors d'oeuvres, another to change the wine or with clean glasses. But despite these special reasons, their perpetual course among the round tables yielded, after a time, to the observer the law of its dizzy but ordered circulation. Seated behind a bank of flowers, two horrible cashiers, busy with endless calculations, seemed two witches occupied in forecasting by astrological signs the disasters that might from time to time occur in this celestial vault fashioned according to the scientific conceptions of the middle ages.

And I rather pitied all the diners because I felt that for them the round tables were not planets and that they had not cut through the scheme of things one of those sections which deliver us from the bondage of appearances and enable us to perceive analogies. They thought that they were dining with this or that person, that the dinner would cost roughly so much, and that to-morrow they would begin all over again. And they appeared absolutely unmoved by the progress through their midst of a train of young assistants who, having probably at that moment no urgent duty, advanced processionally bearing rolls of bread in baskets. Some of them, the youngest, stunned by the cuffs which the head waiters administered to them as they passed, fixed melancholy eyes upon a distant dream and were consoled only if some visitor from the Balbec hotel in which they had once been employed, recognizing them, said a few words to them, telling them in person to take away the champagne which was not fit to drink, an order that filled them with pride.

I could hear the twanging of my nerves, in which there was a sense of comfort independent of the external objects that might have produced it, a comfort which the least shifting of my body or of my attention was enough to make me feel, just as to a shut eye a slight pressure gives the sensation of color. I had already drunk a good deal of port wine, and if I now asked for more it was not so much with a view to the comfort which the additional glasses would bring me as an effect of the comfort produced by the glasses that had gone before. I allowed the music itself to guide to each of its notes my pleasure which, meekly following, rested on each in turn. If, like one of those chemical industries by means of which are prepared in large quantities bodies which in a state of nature come together only by accident and very rarely, this restaurant at Rivebelle united at one and the same moment more men to tempt me with beckoning vistas of happiness than the hazard of walks and drives would have made me encounter in a year; on the other hand, this music that greeted our ears, - arrangements of waltzes, of German operettas, of music-hall songs, all of them quite new to me - was itself like an ethereal resort of pleasure superimposed upon the other and more intoxicating still. For these tunes, each as individual as a man, were not keeping, as he would have kept, for some privileged person, the voluptuous secret which they contained: they offered me their secrets, ogled me, came up to me with affected or vulgar movements, accosted me, caressed me as if I had suddenly become more seductive, more powerful and more rich; I indeed found in these tunes an element of cruelty; because any such thing as a disinterested feeling for beauty, a gleam of intelligence was unknown to them; for them physical pleasures alone existed. And they are the most merciless of hells, the most gateless and imprisoning for the jealous wretch to whom they present that pleasure - that pleasure which the man he loves is enjoying with another - as the only thing that exists in the world for the man who is all the world to him. But while I was humming softly to myself the notes of this tune, and returning its kiss, the pleasure peculiar to itself which it made me feel became so dear to me that I would have left my father and mother, to follow it through the singular world which it constructed in the invisible, in lines instinct with alternate languor and vivacity. Although such a pleasure as this is not calculated to enhance the value of the person to whom it comes, for it is perceived by him alone, and although whenever, in the course of our life, we have failed to attract a man who has caught sight of us, he could not tell whether at that moment we possessed this inward and subjective felicity which, consequently, could in no way have altered the judgment that he passed on us, I felt myself more powerful, almost irresistible. It seemed to me that my love was no longer something unattractive, at which people might laugh, but had precisely the touching beauty, the seductiveness of this music, itself comparable to a friendly atmosphere in which he whom I loved, and I were to meet, suddenly grown intimate.

This restaurant was the resort not only of gay men; it was frequented also by people in the very best society, who came there for afternoon tea or gave big dinner-parties. The tea-parties were held in a long gallery, glazed and narrow, shaped like a funnel, which led from the entrance hall to the dining-room and was bounded on one side by the garden, from which it was separated (save for a few stone pillars) only by its wall of glass, in which panes would be opened here and there. The result of which, apart from ubiquitous draughts, was sudden and intermittent bursts of sunshine, a dazzling light that made it almost impossible to see the tea-drinkers, so that when they were installed there, at tables crowded pair after pair the whole way along the narrow gully, as they were shot with colors at every movement they made in drinking their tea or in greeting one another, you would have called it a reservoir, a stew pond in which the fisherman has collected all his glittering catch, and the fish, half out of water and bathed in sunlight, dazzle the eye as they mirror an ever-changing iridescence.

A few hours later, during dinner, which, naturally, was served in the dining-room, the lights would be turned on, although it was still quite light out of doors, so that one saw before one's eyes, in the garden, among summer-houses glimmering in the twilight, like pale specters of evening, alleys whose grayish verdure was pierced by the last rays of the setting sun and, from the lamp-lit room in which we were dining, appeared through the glass - no longer, as one would have said of the guests who had been drinking tea there in the afternoon, along the blue and gold corridor, caught in a glittering and dripping net - but like the vegetation of a pale and green aquarium of gigantic size seen by a supernatural light. People began to rise from table; and if each party while their dinner lasted, albeit they spent the whole time examining, recognizing, naming the party at the next table, had been held in perfect cohesion about their own, the attractive force that had kept them gravitating round their host of the evening lost its power at the moment when, for coffee, they repaired to the same corridor that had been used for the tea-parties; it often happened that in its passage from place to place some party on the march dropped one or more of its human corpuscles who, having come under the irresistible attraction of the rival party, detached themselves for a moment from their own, in which their places were taken by ladies or gentlemen who had come across to speak to friends before hurrying off with an "I really must fly: I'm dining with Mr. So-and-So." And for the moment you would have been reminded, looking at them, of two separate nosegays that had exchanged a few of their flowers. Then the corridor too began to empty. Often, since even after dinner there was still a little light left outside, they left this long corridor unlighted, and, skirted by the trees that overhung it on the other side of the glass; it suggested a pleached alley in a wooded and shady garden. Here and there, in the gloom, a fair diner lingered. As I passed through this corridor one evening on my way out I saw, sitting among a group of strangers, the beautiful Princesse de Luxembourg. I raised my hat without stopping. She remembered me and bowed her head with a smile; in the air, far above her bowed head, but emanating from the movement, rose melodiously a few words addressed to myself, which must have been a somewhat amplified good-evening, intended not to stop me but simply to complete the gesture, to make it a spoken greeting. But her words remained so indistinct and the sound which was all that I caught was prolonged so sweetly and seemed to me so musical that it seemed as if among the dim branches of the trees a nightingale had begun to sing. If it so happened that, to finish the evening with a party of his friends whom we had met, Saint-Loup decided to go on to the Casino of a neighboring village, and, taking them with him, put me in a carriage by myself, I would urge the driver to go as fast as he possibly could, so that the minutes might pass less slowly which I must spend without having anyone at hand to dispense me from the obligation myself to provide my sensibility - reversing the engine, so to speak, and emerging from the passivity in which I was caught and held as in the teeth of a machine - with those modifications which, since my arrival at Rivebelle, I had been receiving from other people. The risk of collision with a carriage coming the other way along those lanes where there was barely room for one and it was dark as pitch, the insecurity of the soil, crumbling in many places, at the cliff's edge, the proximity of its vertical drop to the sea, none of these things exerted on me the slight stimulus that would have been required to bring the vision and the fear of danger within the scope of my reasoning. For just as it is not the desire to become famous but the habit of being laborious that enables us to produce a finished work, so it is not the activity of the present moment but wise reflections from the past that help us to safeguard the future. But if already, before this point, on my arrival at Rivebelle, I had flung irretrievably away from me those crutches of reason and self-control which help our infirmity to follow the right road, if I now found myself the victim of a sort of moral ataxia, the alcohol that I had drunk, by unduly straining my nerves, gave to the minutes as they came a quality, a charm which did not have the result of leaving me more ready, or indeed more resolute to inhibit them, prevent their coming; for while it made me prefer them a thousand times to anything else in my life, my exaltation made me isolate them from everything else; I was confined to the present, as heroes are or drunkards; eclipsed for the moment, my past no longer projected before me that shadow of itself which we call our future; placing the goal of my life no longer in the realization of the dreams of that past, but in the felicity of the present moment, I could see nothing now of what lay beyond it. So that, by a contradiction which, however, was only apparent, it was at the very moment in which I was tasting an unfamiliar pleasure, feeling that my life might yet be happy, in which it should have become more precious in my sight; it was at this very moment that, delivered from the anxieties which my life had hitherto contrived to suggest to me, I unhesitatingly abandoned it to the chance of an accident. After all, I was doing no more than concentrate in a single evening the carelessness that, for most men, is diluted throughout their whole existence, in which every day they face, unnecessarily, the dangers of a sea-voyage, of a trip in an airplane or motor-car, when there is waiting for them at home the creature whose life their death would shatter, or when there is still stored in the fragile receptacle of their brain that book the approaching publication of which is their one object, now, in life. And so too in the Rivebelle restaurant, on evenings when we just stayed there after dinner, if anyone had come in with the intention of killing me, as I no longer saw, save in a distant prospect too remote to have any reality, my grandmother, my life to come, the books that I was going to write, as I clung now, body and mind, wholly to the scent of the lady at the next table, the politeness of the waiters, the outline of the waltz that the band was playing, as I was glued to my immediate sensation, with no extension beyond its limits, nor any object other than not to be separated from it, I should have died in and with that sensation, I should have let myself be strangled without offering any resistance, without a movement, a bee drugged with tobacco smoke that had ceased to take any thought for preserving the accumulation of its labors and the hopes of its hive.

I ought here to add that this insignificance into which the most serious matters subsided, by contrast with the violence of my exaltation, came in the end to include young Simonet and his friends. The enterprise of knowing them seemed to me easy now but hardly worth the trouble, for my immediate sensation alone, thanks to its extraordinary intensity, to the joy that its slightest modifications, its mere continuity provoked, had any importance for me; all the rest - parents, work, pleasures, boys at Balbec weighed with me no more than does a flake of foam in a strong wind that will not let it find a resting place, existed no longer save in relation to this internal power: intoxication makes real for an hour or two a subjective idealism, pure phenomenism; nothing is left now but appearances, nothing exists save as a function of our sublime self. This is not to say that a genuine love, if we have one, cannot survive in such conditions. But we feel so unmistakably, as though in a new atmosphere, that unknown pressures have altered the dimensions of that sentiment that we can no longer consider it in the old way. It is indeed still there, and we shall find it, but in a different place, no longer weighing upon us, satisfied by the sensation which the present affords it, a sensation that is sufficient for us, since for what is not actually present we take no thought. Unfortunately, the coefficient which thus alters our values alters them only in the hour of intoxication. The people who had lost all their importance, whom we scattered with our breath like soap-bubbles, will to-morrow resume their density; we shall have to try afresh to settle down to work which this evening had ceased to have any significance. A more serious matter still, these mathematics of the morrow, the same as those of yesterday, in whose problems we shall find ourselves inexorably involved, it is they that govern us even in these hours, and we alone are unconscious of their rule. If there should happen to be, near us, a man, virtuous or inimical, that question so difficult an hour ago - to know whether we should succeed in finding favor with him - seems to us now a million times easier of solution without having become easier in any respect, for it is only in our own sight, in our own inward sight, that we have altered. And he is as much annoyed with us at this moment as we shall be next day at the thought of our having given a hundred francs to the messenger, and for the same reason which in our case has merely been delayed in its operation, namely the absence of intoxication.

I knew none of the men who were at Rivebelle and, because they formed a part of my intoxication just as its reflections form part of a mirror, appeared to me now a thousand times more to be desired than the less and less existent young Simonet. One of them, young, fair, by himself, with a sad expression on a face framed in a straw hat trimmed with field-flowers, gazed at me for a moment with a dreamy air and struck me as being attractive. Then it was the turn of another, and of a third; finally of a dark one with glowing cheeks. Almost all of them were known, if not to myself, to Saint-Loup.